This article was first published in the 2017 Conference Issue of Captive Insurance Times

Rule-focused decisions have kept captives from delivering full value.

Fort McMurray, earthquakes, ice storms and floods—we have all seen the headlines about natural disasters and how they affect individuals, businesses, and whole communities. When you are involved in running a captive insurance company, these issues are not just something you read about in the paper, they affect your company, your operations, and your personal credibility as a manager or executive of that operation. The big questions are always: how ready are you, and how do you know you are ready?

But we complied with all the rules

In many captives, risk management has become a generic concept. It focuses on compliance with the rules—whether the captive has enough cash on hand, completed the requisite forms and filings, and followed company protocol. But when a financial disaster hits your captive, it will be little comfort to the board if you tell them that even though they are now insolvent, it is not your fault. After all, you complied with all the rules, what more did they want? The answer is quite a bit, actually. Boards expect management to be prepared and proactive, not merely compliant.

So it is not surprising to find boards asking, just how safe are those government rules? Does the regulatory capital limit protect us from a 1-in-10-year event or from a 1-in-100-year event? The regulatory rules do not answer that question for you. It may very well be that the government rules are more than adequate, but you may want some sort of analysis to support that statement, rather than just take it as a given.

To do this, you need your own assessment of how much risk you are exposed to, how likely you are to draw on your capital, and whether your capital is sufficient. You would also need to determine and justify at what point can you sleep well at night knowing that you are prepared.

Risk management does not mean risk avoidance

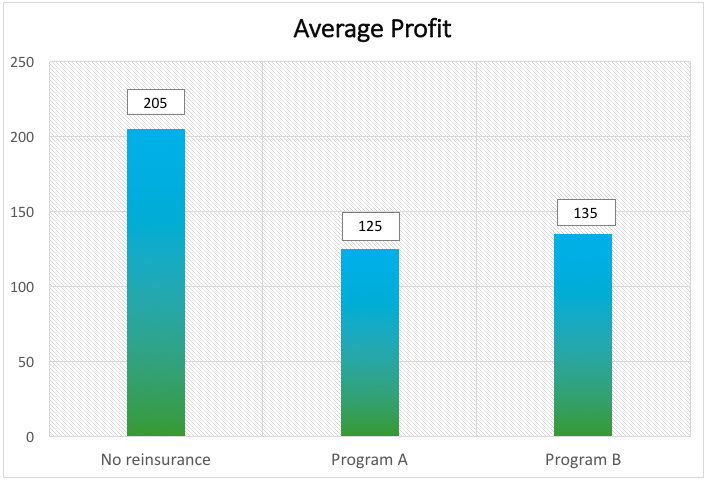

Some companies we work with respond to the concern of adverse claims by passing off even more of their risk to reinsurance companies. A good reinsurance program will certainly reduce your downside risk, but it comes at a cost in the form of reinsurance premiums that are paid even when times are good. What is the right trade-off?

The same risk assessment models that help you decide whether your capital is adequate can and should be used as tools to help you strike an optimal balance of risk and reward in your reinsurance strategy. If you had access to more capital, you could retain more risk and spend less on reinsurance. Conversely, with more reinsurance, you could release some of your capital to your owners or stakeholders.

In determining the optimal reinsurance strategy, the board needs to consider whether it could withstand some year-to-year fluctuations if that produced a lower overall cost, or do they want stable results every year? Adding further sophistication, is there some way to diversify the risks, rather than just think in terms of the one dimensional more/less view?

Complex math, understandable explanations

We, as actuaries, have a tendency to come up with rather complex math as a way to analyze and quantify risk. While some statisticians might disagree, our charts are some of the best in the business.

However, the analysis and charts are just tools, the objective of all this complex math is to help management do a more effective job of managing their business.

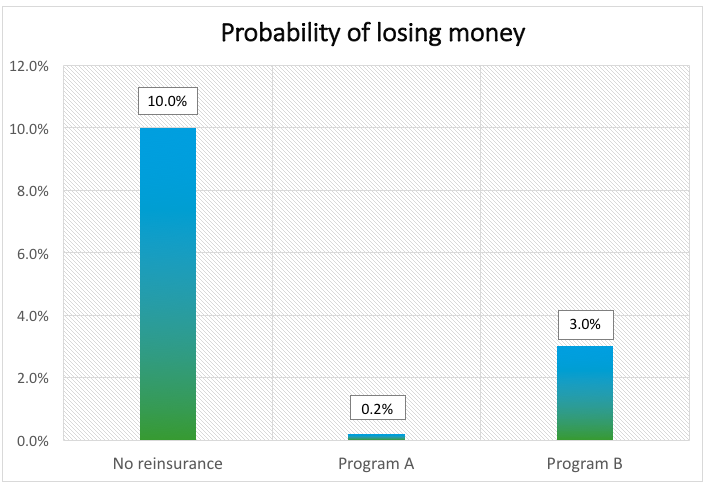

For example, you are running a captive and worried about the downside of adverse claims, and trying to decide between reinsurance program A and reinsurance program B. As a baseline, you also look at results without any reinsurance, what are the odds of losing money overall under none, A, and B options? The answer to this is in the chart below.