Downturn not felt equally in Canada

The OECD also reports that national economies that are more dependent on tourism are not expected to rebound as quickly as those that can rely on a manufacturing base. We can apply that logic to local Canadian economies. And we can infer some relationship between the speed of the recovery and the degree to which employment is by large corporations as opposed to the small businesses that have been hit so hard.

So it is no surprise that a recent analysis by Statistics Canada found that “the economic impacts of the pandemic were not felt equally across the country.”

Specifically, the study found that “Alberta, Saskatchewan and Ontario showed the largest declines in economic activity,” with reduced output in Alberta a result of lower energy prices, while the decline in Ontario was because of tighter coronavirus restrictions.

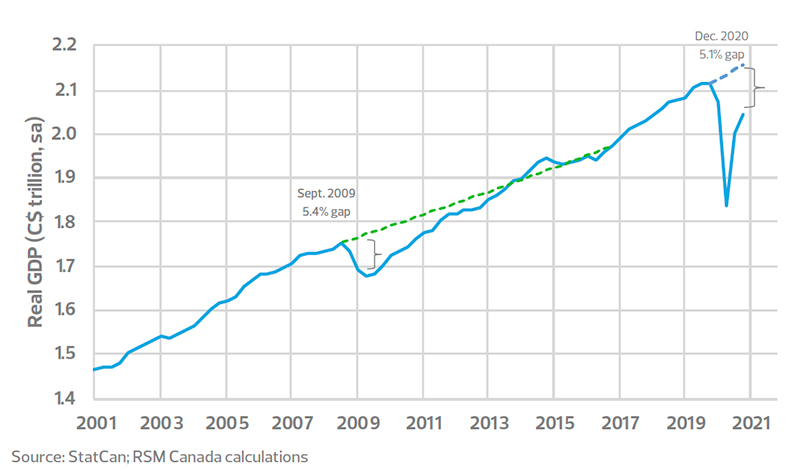

All in all, the OECD anticipates that Canada’s real GDP will grow by 4.7 per cent in 2021 and 4 per cent in 2022. The OECD also finds that a large portion of that growth—and more than any other economy—will be attributable to the American Rescue Plan, the $1.9 trillion pandemic relief package signed into law on March 11. This gives reason to think that further integration of the North American economy is both inevitable and beneficial for all parties.

What a difference an election makes

The November election in the United States paved the way for the passage of additional relief programs in December, while changes in the Senate and the executive branch that followed brought about relief packages that now total 13.1 per cent of U.S. GDP. Compare that to additional fiscal spending equal to 6.8 per cent of GDP in the euro area, 4.1 per cent in Japan and 3 per cent to 4 per cent in Canada, according to the OECD and a BBC report.

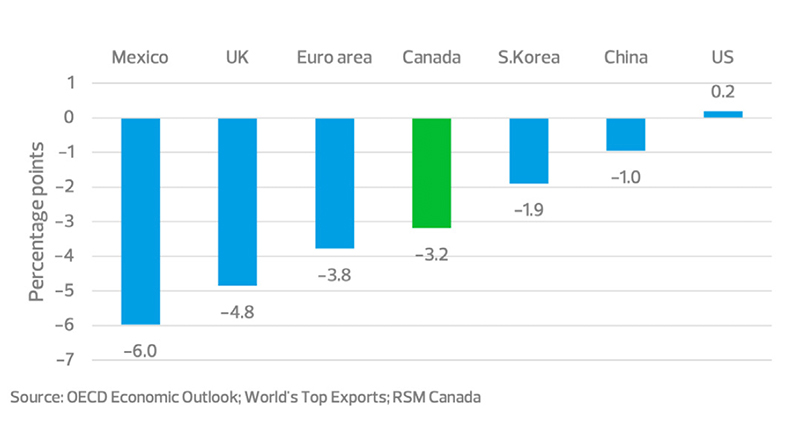

The rebound in the United States is integral to Canada’s recovery, and that should be no surprise. The United States is the recipient of nearly 74 per cent of Canada’s exports, according to the World’s Top Exports, a website that focuses on trade data.

We could expect Canada’s resource extraction and manufacturing to increase as U.S. economic activity increases. And even though net exports account for a small portion of Canada’s national accounts—there are roughly equal amounts of imports and exports—they overlook the significance of higher levels of imports and their implication of higher domestic demand and increased domestic activity.

Increased production activity, whether it is from manufacturing or fracking or technology, will end up supporting downstream service-sector activity and household consumption, particularly once the vaccine has been broadly distributed. Still, we expect that portions of the service sector will lag behind the growth of the overall economy. Lost revenue and employment in small businesses will prove to be irrecoverable, and it will take a while for retooling and retraining to have an impact.

Analysis by StatCan points to these lingering problems that have the ability to affect the health of the labour force, the competitiveness of Canadian business within the global economy, and the sustainability of the recovery. These long-haul issues include:

Impact of the pandemic on the labour force

- Forgone medical treatments and testing

- Worsening mental health, particularly among health- care workers

- Greater financial impact on low-wage workers

- Effects of delayed entry of young people into the labour force and their training

- Decline of 60 per cent in immigration during the pandemic

Competitiveness

- Decline of 13.1 per cent in nonresidential investment at year-end 2020

- The number of unemployed or underemployed workers reaching 1.1 million people as of December 2020

- Business closures, with the greatest impact on small businesses

- Unwillingness of smaller businesses to take on debt

Productivity

For better or worse, the pandemic has most likely hastened the diversification of North American economies toward technology and advanced manufacturing at the same time that those technologies are making possible further integration of industry and the societies of Canada, the United States and Mexico.

StatCan notes increased productivity because of changes in business practices. Productivity “rose in industries that are digital and information and communications technology-intensive, such as wholesale trade; retail trade; finance, insurance and real estate; and other services (including health and education).”

StatCan’s analysis states that while “accelerated shift toward digital assets may result in permanent productivity gains,” it also points out that “more than one-third of office support workers were at a high risk of job transformation.” So there are winners and losers involved in all change, which heightens the need for retraining and increased educational opportunities for all members of the labour force.

Finally, research at StatCan “has found that investments in robotics have not been accompanied by mass layoffs—on the contrary, firms that invest in robots tend to be more productive and hire more workers.”