Co-living is more than a trend—it’s housing infrastructure for a generation priced out of ownership, locked out of quality rentals and in need of social connection. While major cities in other countries move forward with these developments, Canadian efforts remain largely idle despite their potential to address pressing concerns in the market.

Executive summary:

If Canada wants to keep its young people in major cities, it needs to effectively house them.

The co-living housing model offers a scalable, cost-efficient and socially connected approach to urban housing that’s already embraced in cities like Singapore and London.

But in Canada, co-living remains stuck in the pilot phase. This hesitation could prove costly, as Canada will continue to lag in offering the kind of flexible, affordable housing that the next generation needs—and demands—without policy reform and investment.

The case for co-living

Co-living flips the rental model: instead of isolated units, residents get private bedrooms and share kitchens, lounges and bathrooms. This setup is designed with the goal of cutting costs and fostering community.

It’s also greener. Co-living buildings use 10 per cent to 20 per cent less embodied carbon than traditional apartments. But the real win is density; housing more people in the same footprint slashes carbon impact per resident by up to 36 per cent, according to Buildings and Cities.

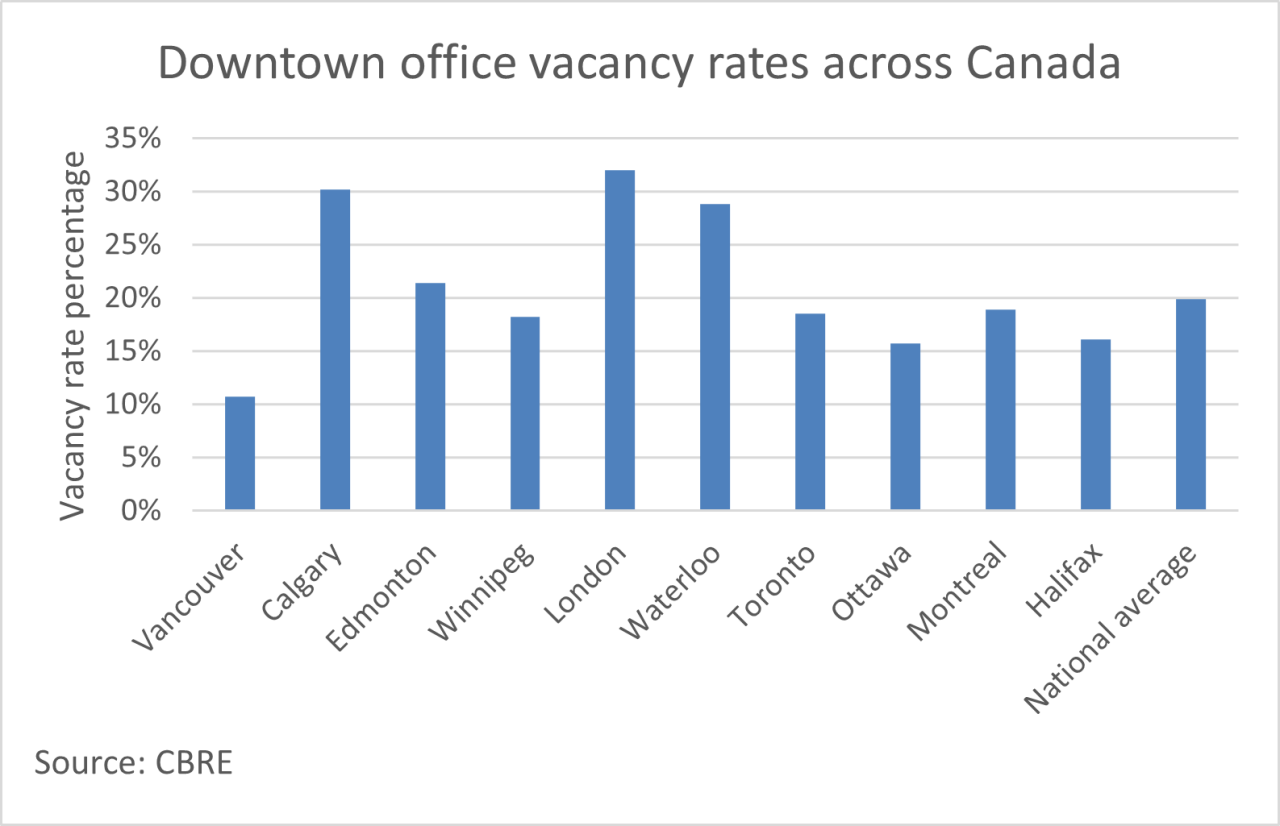

Converting unused office buildings is where the co-living model shines. Repurposing vacant properties can cut construction costs by 25 per cent to 35 per cent, especially when reusing plumbing and restrooms, according to research from Gensler.

These retrofits can accommodate three times as many residents per floor plate without sacrificing daylight or livability. A typical office already has the bones: perimeter offices become bedrooms, boardrooms turn into lounges and washrooms convert to shared baths with showers.

This isn’t theoretical—it’s a ready-to-build solution for Class B and Class C office space sitting empty in downtown cores.

While the world builds, Canada debates

Singapore has recently delivered over 9,000 co-living units designed for affordability, density and community, while Savills research reports around 9,000in Great Britain—with another 5,500 under construction.

Meanwhile, Canada remains stuck in analysis mode. Housing demand is growing and capital is circling, but outdated regulations and financing frameworks are holding the market back.

This adds to the multifaceted challenges facing a generation of Canadians. Youth unemployment hit 13.5 per cent in June, the highest since 2014 outside of the pandemic, according to Statistics Canada.

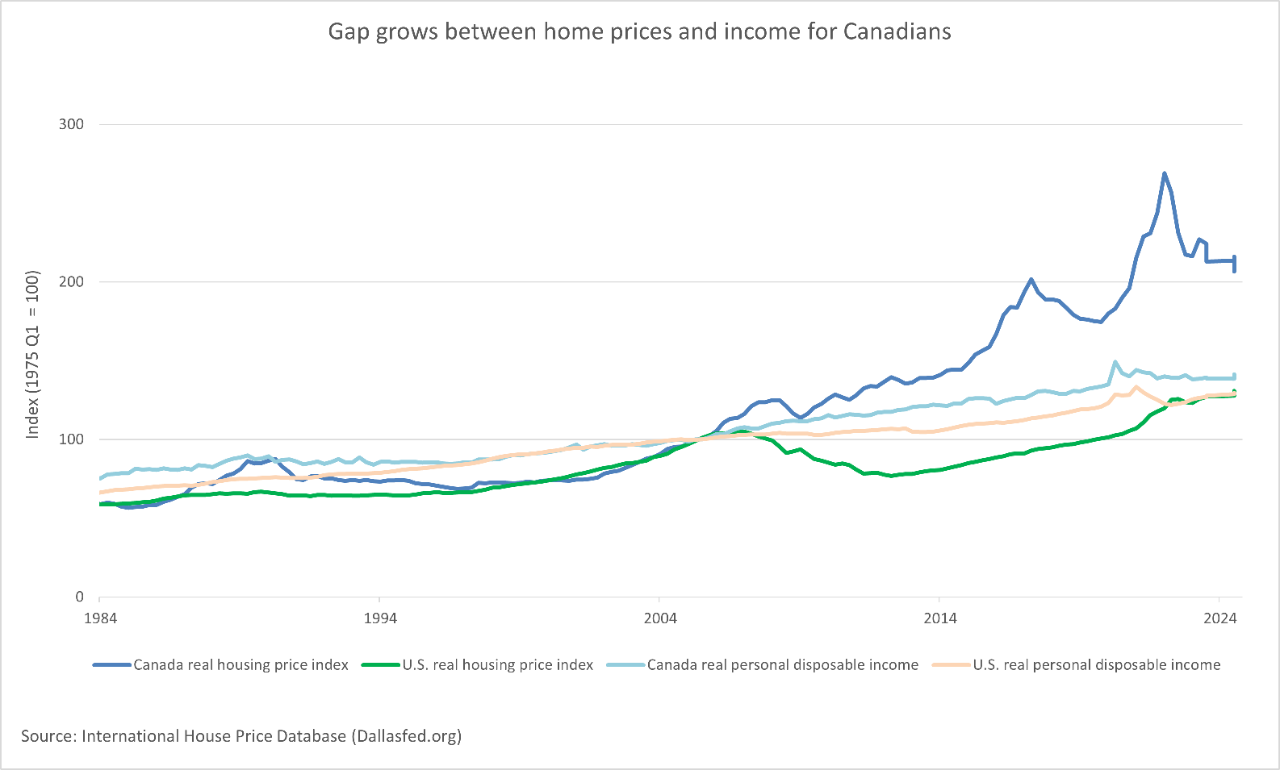

Housing? Worse. Canadian home prices have decoupled from real personal disposable income (RPDI) far more severely than in the U.S., according to the real housing price index (RHPI).

The emotional effects are also notable. The 2024 World Happiness Report ranked Canadians over 60 as eighth globally for life satisfaction—but those under 30 placed 58th; there is a similar 50-place gap for the U.S.

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation links youth loneliness to social media and weakened in-person connection. Developing co-living spaces—with their inherent affordable, community-focused design—could be helpful in the face of these myriad challenges.

Capital is interested—but waiting on government

In Canada, institutional capital is already investing in co-living—but abroad. Pension funds are backing co-living ventures in Europe and Asia.

What’s missing domestically is regulatory certainty. Most of Canada’s housing finance programs, including Canada Mortgage Housing Corporation (CMHC) incentives, are structured around traditional dwellings as opposed to shared-housing models.

This still encourages micro-unit condos rather than co-living despite the fact that condo sales have plunged 75 per cent in Toronto and 37 per cent in Vancouver since 2022, per CMHC. Most of those units were built for investors rather than residents—and now the market is experiencing a hard correction.

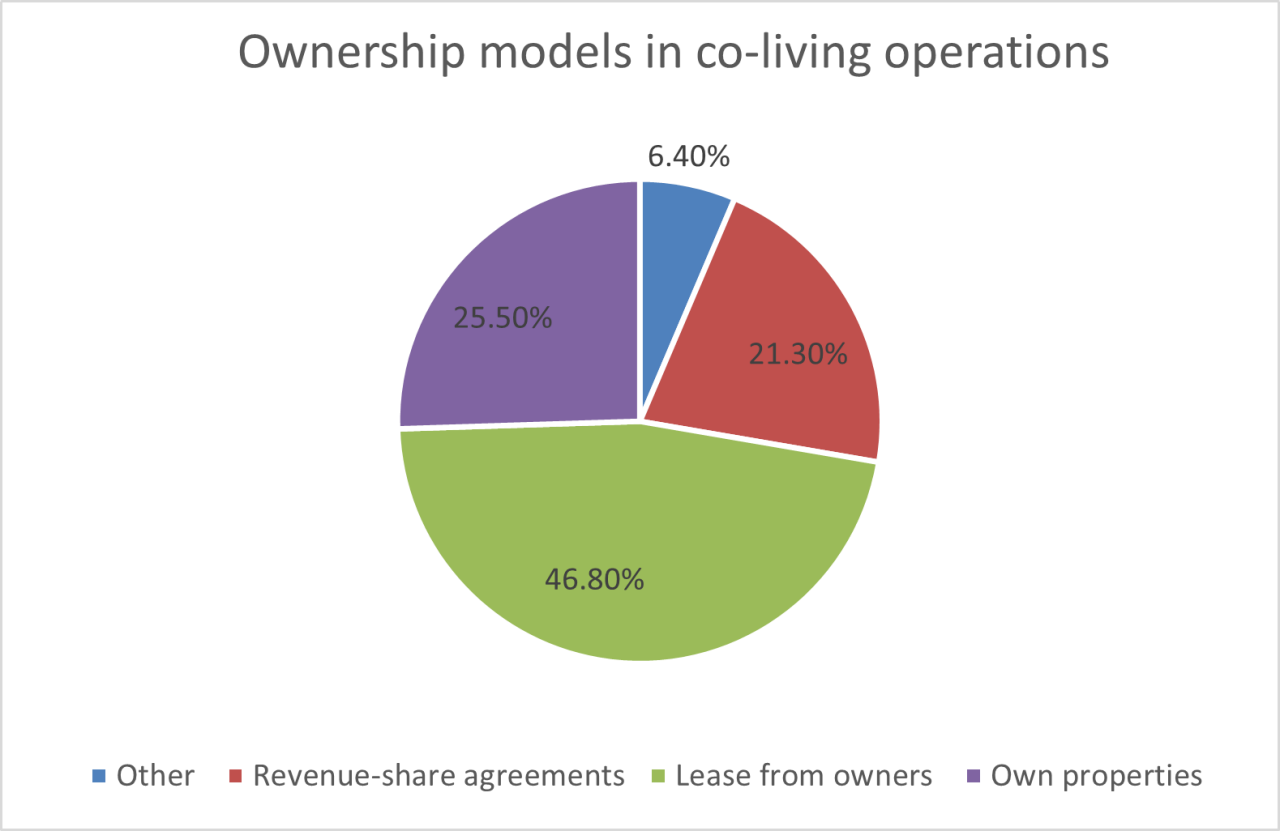

Globally, co-living operators tend to use asset-light models, such as master leases or revenue sharing. Only 25 per cent own their buildings outright, according to Everything CoLiving’s Global Report.

This creates a window for struggling office landlords to partner, rather than sell.

The Toboggan Flats demonstration project is a rare Canadian effort to bridge the gap by converting empty offices into affordable co-living through partnerships with the community housing sector.

Backed by CMHC innovation funding, the team plans to complete its first office-to-residential conversion in just nine months.

But this initiative is limited because it is simply a demonstration. Without reforms to financing, zoning and insurance, scaling this model across Canada remains a challenge.

The takeaway

Co-living isn’t just a market play—it’s a generational imperative. This model addresses three of the most critical gaps in Canada’s urban housing system: affordability, speed and social connection.

Calgary’s downtown incentive program represents a strong start, but broader action is needed. In the U.S., reforms are already underway; several cities have reclassified office-to-residential conversions early in construction to reduce tax burdens and accelerate development.

Retrofitted buildings also lease for less, get delivered faster than ground-up builds and foster community in ways conventional apartments rarely do.