The U.S. dollar's dominance as the world's reserve currency is likely to continue, supported by stability, global demand, and the absence of viable alternatives.

Key takeaways

Calls for the end of dollar preeminence are premature, as major economies still rely on the dollar's stability and liquidity for their own economic welfare.

The rules-based international financial system heavily depends on the U.S. dollar, with attempts at de-dollarization facing significant challenges and limited success.

Recent talk that China, India and Russia are settling purchases of oil in non-dollar denominations has generated speculation that the U.S. dollar's days as the world's reserve currency are ending.

This is nothing new. There were similar discussions during the financial crisis 15 years ago and, more recently, during the cryptocurrency bubble.

However, most current measures of dollar valuation suggest continued dollar strength.

Its strength is no small matter to the Canadian economy. Canada is the United States' biggest trading partner, shipping nearly all of its energy production, to cite just one industry, south of the border to be consumed, processed or exported.

A U.S. dollar that is the global reserve currency brings stability and predictability to these markets. Without it, Canada and its major industries would pay a premium to find a home for many of its exports.

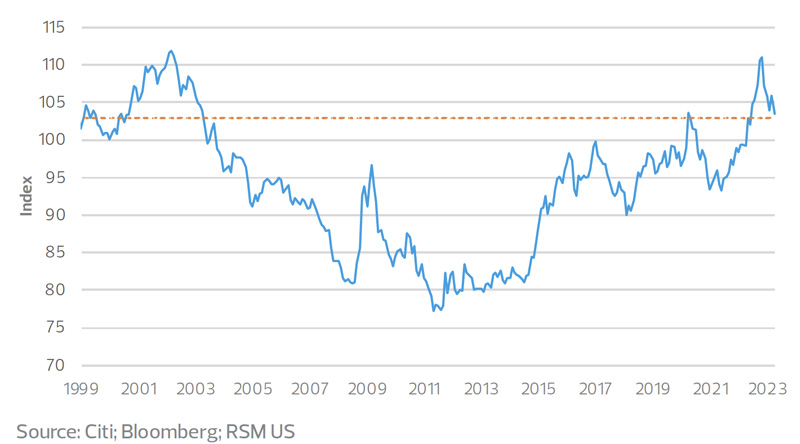

Citi U.S. dollar real effective exchange rate index

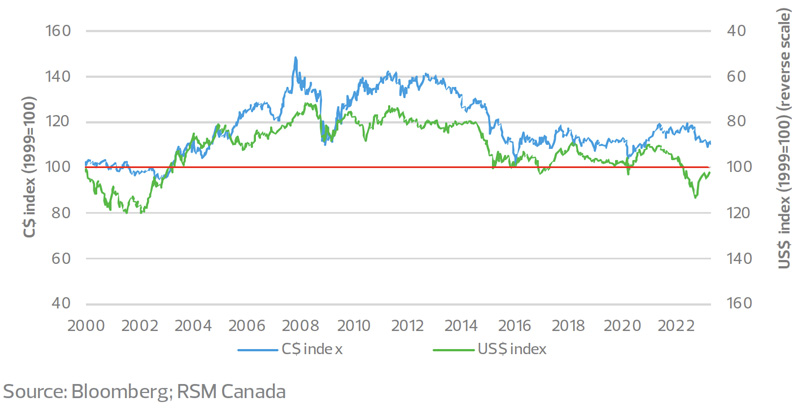

We can see this stability in the U.S. and Canadian trade-weighted currency indices.

Using 1999 as a base period, we show the reverse relationship between the intertwined trading partners.

When the U.S. currency appreciates, the Canadian currency depreciates. But after the collapse of oil and commodity prices in 2014, the range of trading for both currencies narrowed as the economies coalesced, allowing monetary policies to move in sync. We expect this relationship to continue.

The biggest diversion between the currency indices since 2012—14 came last year when oil prices spiked and international investors reacted to the rapid response of the Federal Reserve to inflation.

Since then, both currencies appear to be moving back within their narrow trading ranges of the past nine years.

Citi U.S. dollar real effective exchange rate index

Using Citi's real effective exchange rate index, the American dollar in April was below its recent peak of 111.90 in October. Yet 103.81 is well above where it has been for most of the past 20 years. The index measures the value of the dollar, where 100 is neutral.

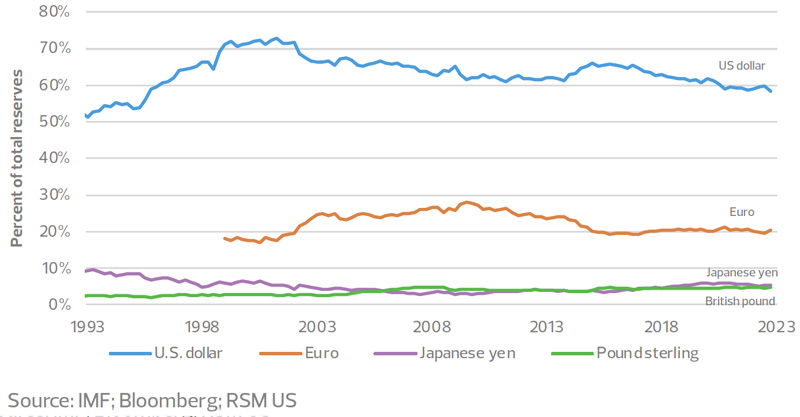

The dollar accounted for roughly 60 per cent of global currency reserves at the end of last year, down from its recent peak of just above 70 per cent in the first part of this century but well above the 50 per cent of 30 years ago.

We find the recent discussion around the end of the U.S. dollar's dominance bereft of any linkage to the reality of international finance and understanding of the dollar's role as the anchor of the rules-based order that governs global economics.

Rather, the recent conversation is stoked by global grievances about the relative disparity of economic power and the dead end that some economies find themselves in.

While these economies may desire an end to dollar dominance, they are experiencing major challenges on their own. Calling for an end to dollar preeminence is premature at best.

The global financial system rests upon the stability of the dollar and the large trade deficit of the United States.

In essence, the United States exports dollar stability to obtain goods and services at a cheaper price, and in doing so enhances the welfare of its citizens. In return, the major trading economies get to hold a currency that is sounder than their own—think of the Chinese yuan, also known as the renminbi, which relies upon the depth of global liquidity markets based on the dollar to maintain that country's currency regime. That reliance, in turn, reinforces the dollar's hegemony.

In short, the economies that run surpluses need that dollar-based demand from the United States to make up for their own weak consumption and high savings rates.

Canadian and U.S. dollar trade-weighted indices

China, which accounts for 2.7 per cent of global reserves, is a case in point. For the yuan to become a true reserve currency, China would have to liberalize it. Such a loosening would result in a decline in the ability of the regulatory authority to control credit, and in relinquishment of control of its capital account and current account.

China would have to be willing to alter its economic framework so that its economy plays the same role as that of the United States. Given China's current political arrangements, that will not happen. And the dollar will remain dominant.

Moreover, the soft power of the United States is too often discounted. The rule of law, foreign direct investment—with the notable exception of China and Russia—and the dollar's support of the rules-based order all reinforce U.S. economic and financial power.

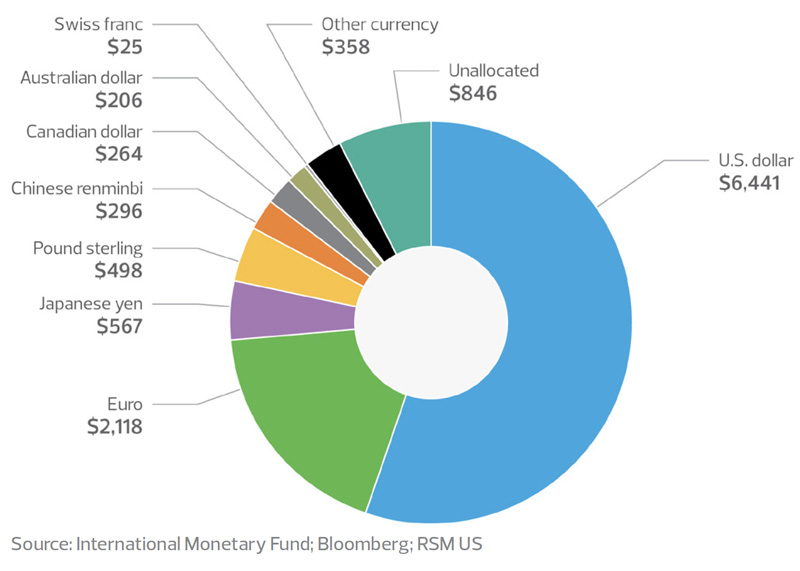

Global foreign exchange data

The vast majority of international trades, almost 90 per cent, are invoiced in U.S. dollars or euros, according to a recent analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

That corresponds to the 80 per cent of total foreign exchange reserves allocated to the dollar and euro held by central banks at the end of last year. The dollar accounted for 60 per cent and the euro 20 per cent.

China, Russia, India and Saudi Arabia are not in any economic shape to support such a change in the rules-based order.

Despite the global economic growth over the past three decades, the current order is simply not going to change at the scale necessary to supplant the American dollar and the global order it supports.

Only three other economies have some of the qualities needed to support a reserve currency: the eurozone area, Japan and the United Kingdom.

But none of those have financial markets with the depth and liquidity to form the backbone of international finance and trade.

In the early 2000s, the percentage of dollar and euro reserves was as high as 90 per cent, with the gradual decline since then most likely occurring because of increased trade among smaller economies and, more important, their reduced reliance on the foreign issuance of debt.

The International Monetary Fund also notes that as stockpiles of foreign currency reserves grow, so does the case for portfolio diversification.

Currencies of smaller economies that have not traditionally figured prominently in reserve portfolios but offer high returns and stability—like the Australian and Canadian dollars, Swedish krona, and South Korean won—account for three-quarters of the shift from dollars.

Other IMF analysis notes that the dollar is the dominant reserve currency by default. The absence of an alternative to the safety of dollar-trade invoicing, international funding markets and the large supply of guaranteed Treasury bonds suggest that the dollar's role in the global economy is secure.

Currency composition of foreign exchange reserves

IN BILLIONS OF U.S. DOLLARS AS OF DECEMBER 2022

What determines a reserve currency

A reserve currency needs to be stable and safe, a store of value and a medium of exchange, and widely accepted and trusted.

This is according to an analysis by Vivek Joshi in India's Sunday Guardian, which notes additional societal and economic criteria for a global reserve currency, including:

- The stability of the political system of the issuing country

- The size and prospects of the economy

- Global integration of its markets and economy

- A transparent and open economic system

- A credible legal system

- The quality of its sovereign debt

- The ability to bear costs associated with a reserve currency

- The size, depth and liquidity of financial markets

There is good reason for the shared dominance of the dollar and the euro, and, to a lesser extent, the Japanese yen and the British pound.

They represent the major economic centers of the world and operate within the rule of law.

There are good reasons why other currencies do not yet qualify. They are either too small (Switzerland), operate under totalitarian regimes (Russia and China), or allow for protectionism (India).

Finally, a reserve currency needs to be market-based, free-floating and, most important, stable. That rules out cryptocurrencies, which are prone to wild swings and for the most part live outside the regulatory system.

There have been two major reserve currencies in modern times: the British pound until World War II, and the American dollar for the past 75 years.

The euro has gained status since its inception as a single currency in 1999, now bolstered by the increase in transaction demand for it by developing economies in Eastern Europe and Africa.

Foreign exchange reserves by currency as a percentage of total allocated reserves

Stability of the dollar

The traditional U.S. dollar index is the weighted average of the exchange rates of six developed economies: the eurozone, Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada, Sweden and Switzerland.

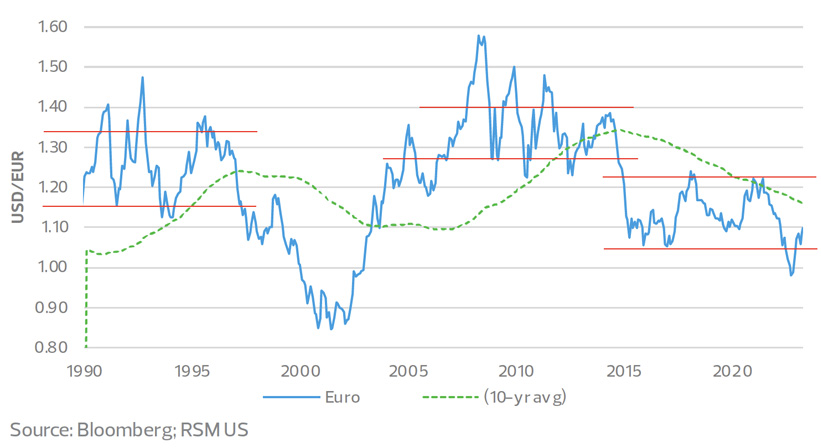

The euro has a weight of 58 per cent in the dollar index and a correlation coefficient of 0.98 based on monthly values of the dollar index and the euro since 1980.

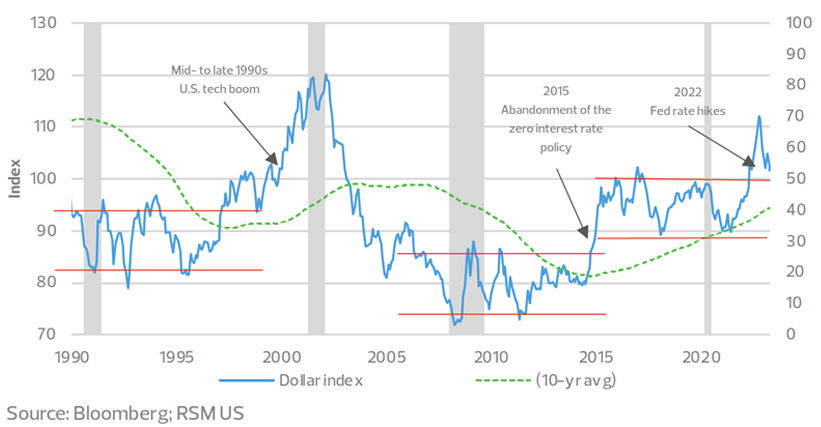

Since 1990, the dollar index and the euro have experienced three periods of trading within narrow ranges, interrupted by consequential events that have altered either the demand for U.S. assets or the mix of monetary and fiscal policies.

As we show, the pattern of range trading followed by a breakout of the exchange rates became apparent when advances in desktop computing created the technology boom in the 1990s.

A bust followed, along with a period of the dollar range trading at a lower level from 2005 to 2015 as the sluggish U.S. economic recovery trudged along.

Late 2015 was the next turning point, when the Federal Reserve began to normalize interest rates while the monetary authorities in Europe and Japan kept rates at or below zero.

That shift in monetary policy provided a dramatic boost to the dollar as it quickly moved to a higher trading range that lasted until March 2022.

This most recent breakout was the result of the dramatic introduction of a dollar-friendly policy mix last year.

The American government was in the midst of the greatest fiscal response to an economic crisis since the Great Depression when the Federal Reserve rapidly hiked its policy rate. The dollar soared while the European Central Bank (ECB) had a lagging response to inflation and the Bank of Japan maintained its yield-curve control.

The mix of tightening monetary policy and expansive fiscal spending pushed U.S. interest rates higher . With interest rates still near zero in Japan and Europe, the dollar and dollar-denominated assets became that much more attractive.

Global investors looking for higher returns on investments in U.S. securities and business opportunities, augmented by the self-fulfilling higher currency return, flocked into dollar-denominated assets.

Breakouts from range-trading periods in the U.S. dollar index

Where do we go from here?

The differences in monetary policy between the United States and Europe were unlikely to last forever, as evidenced by the dollar's peak most likely occurring last September and the euro now trading back within its 2015−22 range.

We can attribute the strengthening of the euro over the past seven months to the shrinking spread between the Fed's and ECB's policy rates as the ECB continues to respond to its 10 per cent inflation rate.

There is also the newfound ability of Europe to survive the winter with diminished supplies of energy and its efforts to expand NATO. All of this is buffered by the uncertainty surrounding the war in Ukraine.

We do not expect that an economic slowdown will drastically affect the relative policy mixes of the United States and its trading partners.

Instead, the most important factor in exchange rate stability has been the synchronization of economic growth and the coordination of monetary policy among developed nations. This is unlikely to change.

There are bound to be deviations in policy (e.g., Japan's likely end to yield-curve control) that will continue to affect individual currencies.

And there will be differences in the transaction demand for currencies, with the currencies of economies dependent on resource extraction (see Canada and Australia) more affected by trends in economic growth and in particular by the price of energy (see Japan again).

Still, we need to recognize that previous large shifts in the dollar's value were attributable to innovation breakthroughs, financial busts or consequential changes that have affected the demand for U.S. assets.

Since 2015, the range of dollar trading has been between $1.05 and $1.20 against the euro, with a $1.12 center

of gravity.

By any measure, the dollar at $1.10 is within range of its longer-term average value. Its movements beyond that range will depend on inflation, economic growth and monetary policy, all relative to what happens in the rest of the world.

Whether it breaks out below or above its recent range will depend on the next round of innovation or the next crisis.

The next crisis could occur as early as June. The debt ceiling debate will devolve into an existential crisis only if Congress allows the United States to default on its debts this summer.

There are no viable or readily available alternatives to the U.S. dollar being the world's reserve currency. The result would be chaos in international trade and finance, with the cost borne by American businesses and consumers.

We also expect to hear calls for the abandonment of the regulation provided by central banks and the abandonment of traditional currencies in favour of cryptocurrencies.

Crypto advocates attribute crypto instability to growing pains and argue that, like traditional currencies, crypto fluctuates according to demand. But the demand for any currency is based on economic and societal factors underlying the currency and not purely on speculative behaviour.

Range-trading periods in the U.S. dollar/euro exchange rate

Previous attempts to de-dollarize

The efforts of the United States, the European Union and Japan to use their prodigious financial and economic power to address the Russian invasion of Ukraine have rekindled the ideal of de-dollarization.

This is not exactly a new phenomenon. Latin American and Middle Eastern economies have attempted to exit the dollar-based system.

Since the 1970s, Latin American nations like Chile and Venezuela have tried to exit the dollar-based global financial order. Venezuela has for some time attempted to purchase oil in Chinese yuan.

During the past half-century, Iraq and Libya attempted to move away from the dollar through the euro and a pan-African solution.

And we should all remember the entreaties by Japan in the late 1980s for the United States to consider a broader role for the yen before the bursting of the Japanese financial bubble.

That request was politely rebuffed by the Reagan administration. And one should expect no different from the current and subsequent American governments.

While we recognize that the international economy has been altered by geopolitical tensions, shifting supply chains and the return of industrial policy, we just do not see a major alternative to the rules-based system supported by the American dollar.

In fact, the only thing that would really alter the current international status quo would be for the United States to default on its debt. But that is another story for another day.