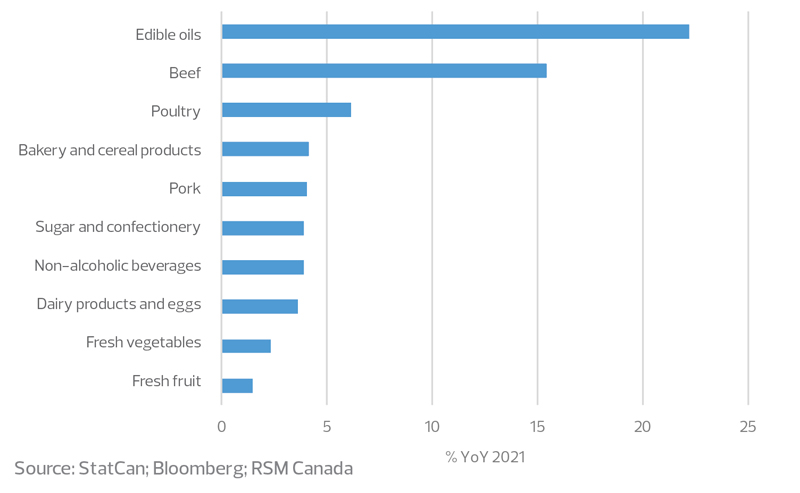

For consumers, the result is food prices that far outpaced core inflation last year, with the most dramatic increases in edible oils (22.2 per cent) and beef (15.4 per cent), while other items had more moderate increases like poultry (6.2 per cent). Some items had modest increases more in line with target inflation like fresh vegetables (2.3 per cent) and fresh fruits (1.5 per cent).

Worker shortage

Even before the pandemic, jobs in the food sector already had trouble attracting workers as they tended to be lower paid with few benefits and physically demanding conditions. This is true for workers in food processing plants and grocery stores, as well as restaurants.

The downsides have been exacerbated by the pandemic as workers face an elevated risk of infection. The outbreaks in 2020 in processing plants showed that many workers did not receive adequate protection from COVID-19.

The pandemic prompted an unprecedented number of people to switch industries and find new careers. The food sector has been no exception as workers leave to seek higher pay and job security.

The fast-spreading omicron variant resulted in droves of workers having to isolate, leading to an acute worker shortage. While overall demand for food did not decrease, the workforce this year has had a temporary but prominent reduction in size.

Time sensitivity a key issue

While few industries are immune from supply chain disruptions, the food sector is even more susceptible because of the perishable nature of groceries.

Starting Jan. 15, unvaccinated American truck drivers have not been able to enter Canada, while Canadian truck drivers re-entering Canada from the United States must be tested and quarantine themselves. The policies have been met with rising protests.

With such a shortage of truck drivers, even a small drop in the number of cross-border drivers could further strain the food supply chain. The RSM Canada Supply Chain Index notes that Canada's supply chain health took a turn to the worse in the past couple of months, while remaining well below sufficiency level.

In addition to the floods and landslides in British Columbia, other factors also exacerbate delivery times. High COVID-19 case counts mean there are fewer workers checking inventory, moving boxes and stocking shelves. As a result, everything takes longer.

Longer delivery times translate to more food waste, which could increase prices even more as businesses pass on the cost to customers.

Implications for the Canadian economy

Since food is a necessity, consumer behaviour is affected not only by current food prices but by consumers' anticipation of future prices. Many consumers expect food prices to continue to rise substantially this year, which will lead to behavioural shifts that hinder the economic recovery.

Households will switch to eating out less and shopping at discount stores, as well as substituting items that had the most increases over the past years - like meat - for lower-priced items.

In addition, when consumers have to spend more money on food, they have less money left for discretionary spending on things from entertainment to electronic devices. This presents yet another barrier in the recovery as households keep their consumption in check.