Declining labour force participation rates, an aging population and declining fertility rates mean that Canada must rely on immigration – rather than natural growth – to replenish the labour pool.

Key takeaways

Canadian policymakers are aiming to bring in more than 400,000 immigrants per year between 2022 and 2024 following the growth immigration has spurred in the millennial and Gen-Z workforce.

Canada must streamline the accreditation process if it wishes for skilled immigrants to fill the labour gaps that are most glaring, such as in the health care industry.

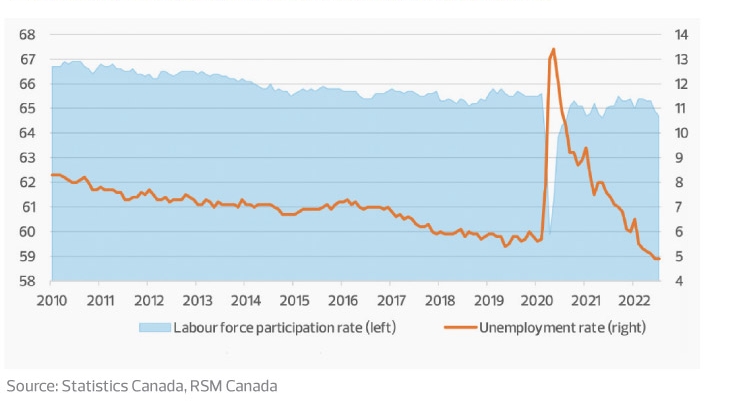

There is no denying it: Canada is experiencing a historic labour shortage. The job market has been running hot for months, with the unemployment rate falling to 4.9 per cent, the lowest on record.

The pandemic and subsequent reopening have been the catalyst. At the onset of the pandemic, workers were laid off, turned to self-employment or retired early. When the economy reopened, organizations were unable to find enough workers to meet pent-up demand for goods and services.

The shortages have hit certain industries particularly hard, including health care, hospitality and food services, and trucking.

Even as the economy shed jobs over the summer, the decline stems from workers choosing to leave rather than businesses needing fewer employees. More than 200,000 people have left the workforce since March, resulting in the labour force participation rate dropping to 64.7 per cent.

Labour force participation and unemployment rates

In the long run, the challenge runs deep. A fundamental demographic shift is taking place in Canada as the population ages and fertility rates decline. Combined, this means fewer workers.

In this environment, even when unemployment declines, labour force participation also goes down because people retire, a trend that will not reverse as the population over 65 increases.

Simply put, Canada cannot replenish the labour pool through natural growth.

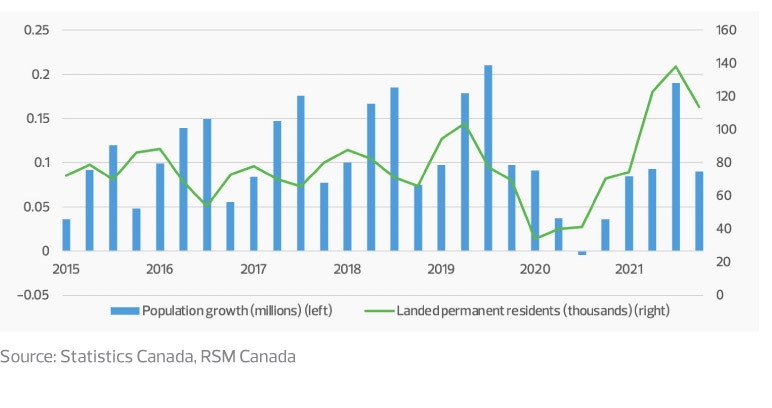

Immigration as a solution

Part of the answer lies in immigration. Already, whatever growth has come in the millennial and Gen-Z workforce has been because of immigration. This is not lost on policymakers, who have already devised several economic pathways and outlined ambitious goals for bringing in more than 400,000 immigrants per year between 2022 and 2024.

And the benefits of immigration go beyond merely solving the worker shortage. Immigrants have been shown to increase labour productivity, something Canada cannot afford to ignore as labour productivity in Canada might fall to last among countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in just a decade.

But having an open immigration policy alone is not enough to address the long-term labour shortage.

First, the majority of recently landed permanent residents are already living and working in the country, so the 400,000 target does not represent the true number of people coming from abroad.

Immigration and population growth

Even those already living and working in Canada are often unable to fill the gap of demand for labour despite being qualified and having relevant work experience.

Employers are sometimes hesitant to hire workers if they do not have Canadian work experience and can be quick to dismiss workers with experience abroad, which only narrows the available pool of experienced hires.

More important are the barriers from government and industry associations. Certain professions, including the ones where shortages are most pressing, require licensing to practice.

For professionals trained abroad, the road to accreditation to practice in Canada is fraught with red tape, designed to stop and discourage rather than facilitate.

As a result, Canada faces a conundrum: While severe shortages persist in certain industries, workers fully qualified to fill these vacancies are often forced to sit on the sideline.

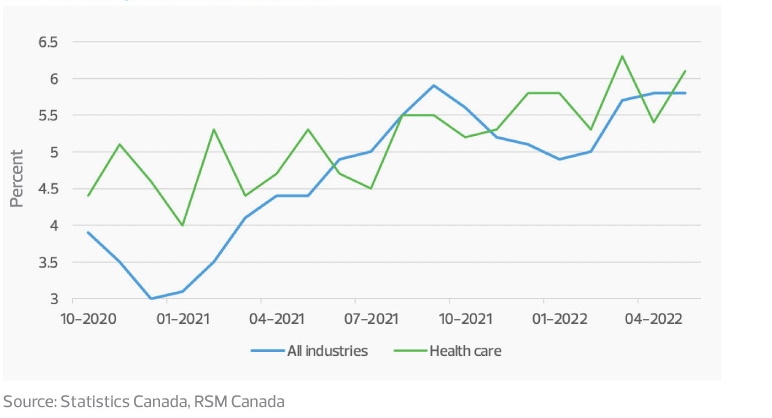

The example of the health-care industry

Health care is a place where this need for workers plays out most clearly. In May, there were 143,000 vacancies in health care, up 20 per cent from a year prior. In July alone, 22,000 health care workers left the field despite strong demand.

The pandemic laid bare the crumbling health care system: long waits, delayed routine care resulting in serious conditions as patients were left untreated, and the temporary closure of emergency rooms because of a

lack of staff. They are all symptoms of an acute shortage of workers.

Yet the accreditation process for nurses and doctors trained abroad is inefficient. The registration process for internationally educated nurses to work in Canada can take years. Doctors educated and having practiced outside Canada must redo their entire residency program, which takes years, in addition to passing Canadian medical exams, to obtain their license.

Job vacancy rate in health care

The Great Resignation in health care has had far-reaching consequences. As health-care workers quit because of burnout, their departure intensifies pressures on the remaining workers, who in turn become burned out and are also driven to quit.

The impact extends to every part of the economy. A crumbling health care system translates to more sick people. When workers or their family members get sick, workers have to take time off, cut back on hours or even quit their jobs. This worsens the labour shortage across the country, and no single industry is immune.

The takeaway

A recession will not magically solve the chronic worker shortage. While the service industry might see the shortage ease as demand for labour slows, doctors and nurses train for years before they can practice. For this reason, a recession will not translate to an influx of health care workers. Neither would the privatization of health care, as a quick look at the United States shows.

To tackle the challenge of labour supply, treating and compensating workers well to improve retention would be a start.

But government, industry associations and organizations need to go further and streamline the accreditation process so that workers educated abroad can fill much-needed roles in Canadian society. Only then can Canada hope to have meaningful growth in labour supply and productivity.

RSM contributors

The Real Economy Canada

A quarterly economic report for middle market business leaders.

Industry insights

Industry-specific insights for the middle market.