The Canadian economy has bounced back strong from pandemic lockdowns, as pent-up consumer demand and government support have fueled GDP growth in every quarter since the third quarter of 2021.

Key takeaways

Inflation and a rising unemployment rate, combined with persistent labour and housing shortages, present elevated risk that Canada could enter a recession early next year.

Businesses should expect the Bank of Canada to continue raising rates for the rest of the year rather than easing them prematurely.

The Canadian economy has had a robust recovery from the lockdowns of the pandemic as pent-up consumer demand and generous government spending have fueled growth. But now with rising inflation, especially in food and energy prices, and a historically tight labour market, that growth is slowing.

The Bank of Canada, like many central banks around the world, has been aggressively raising interest rates to tame inflation. But raising rates has consequences.

In the best-case scenario, the Bank of Canada would reduce discretionary spending enough to stabilize prices while the economy grows, though at a slower pace. In the worst-case scenario, economic growth would completely stop as spooked consumers rein in spending, and the economy tumbles into recession.

We expect the Bank of Canada to continue its effort to restore price stability despite the costs.

In the coming months, more people will become unemployed, which will present a challenge for low-income households as they try to keep up with the rising cost of living. Even with these challenges, though, Canada is not currently in a recession, which is defined as a significant decline in economic activity lasting more than a few months.

A rule of thumb frequently cited to define a recession is two consecutive quarters of contraction in gross domestic product. In contrast, Canada’s GDP has been growing every quarter since the third quarter of last year, at a rate of 6.6 per cent in the fourth quarter last year, 3.1 per cent in this year’s first quarter and 3.3 per cent in the second quarter.

Real GDP growth

But having two consecutive quarters of contraction is not a hard-and-fast definition. Rather, to determine whether the economy is in recession, other indicators need to be considered. These include payroll employment, the unemployment rate, real income and spending, and industrial production.

By most of these indicators, the economy is in a downturn rather than a recession. The unemployment rate of 4.9 per cent remains at a historic low despite the modest decline in job numbers over the past two months.

The industrial sector has been robust as Canadian producers reap the benefits of strong global demand for metals and energy.

But there are elevated risks that Canada could enter a recession early next year after modest growth this year.

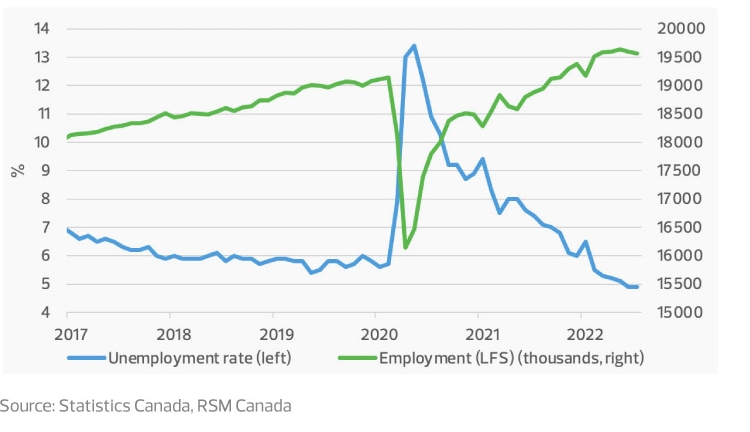

The labour market

The unemployment rate stands at its lowest level since 1976, giving the Bank of Canada some leeway in normalizing interest rates. That said, if the demand for labour declines, the unemployment rate will creep up.

The economy shed 43,000 jobs in June and another 30,000 in July because of workers leaving the labour force rather than because of layoffs. Job declines came entirely from the services-producing sector, including educational services, and health care and social services.

There are currently more than 1 million job vacancies, mostly in the food and services sector and in health care.

The long-term challenge remains the worker shortage, and Canada relies on immigration rather than natural growth to feed the expansion of its labour force.

Employment and unemployment rate

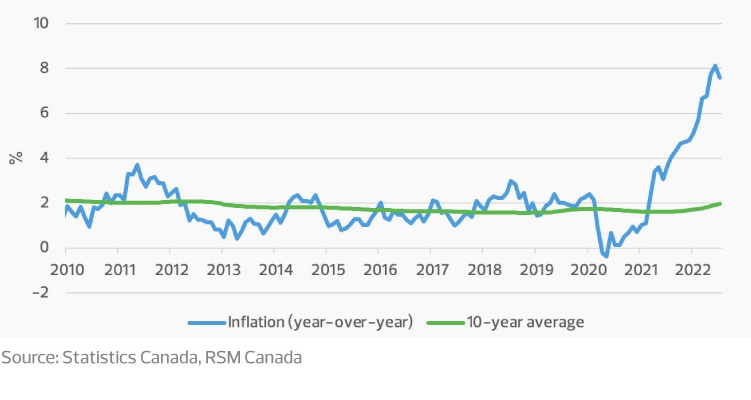

Inflation expectations

Canadian households and businesses are used to low inflation, which has been at or below the 2 per cent target for more than a decade. Now, with shocks to the global supply chain and geopolitical turmoil, inflation has been elevated for more than a year, rising to the highest levels since the early 1980s.

Though there are signs that inflation might have peaked—it eased to 7.6 per cent in July after hitting 8.1 per cent in June—it will take a while to slow as the war in Ukraine grinds on and the labour market remains tight.

In response, the Bank of Canada has implemented aggressive rate hikes to tackle inflation.While short-run inflation expectations have climbed, as seen in the wage growth that has deviated from the 2 per cent mark, long-run inflation expectations remain relatively anchored.

At the Federal Reserve’s recent symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, the world’s top central banks declared that inflation is here to stay and will require forceful actions. Businesses should expect the Bank of Canada to continue raising rates for the rest of the year rather than easing them prematurely.

The housing market

In few places is the turn of the business cycle as apparent as in the housing market, which has cooled substantially because of higher borrowing costs. Construction projects are being cancelled or put off. Across the country, listings and home prices are falling, a stark contrast from the overheated market of just under a year ago.

Still, the housing shortage will not be resolved anytime soon; if anything, it will become even worse now as builders pull back. The housing affordability crisis remains as would-be buyers resort to renting and Canadians who fled the cities due to the pandemic now start to return.

Canada still needs to build hundreds of thousands of units to house its people, and once again low-income households are hurt the most in the affordability crisis.

Consumer price inflation rate and 10-year average

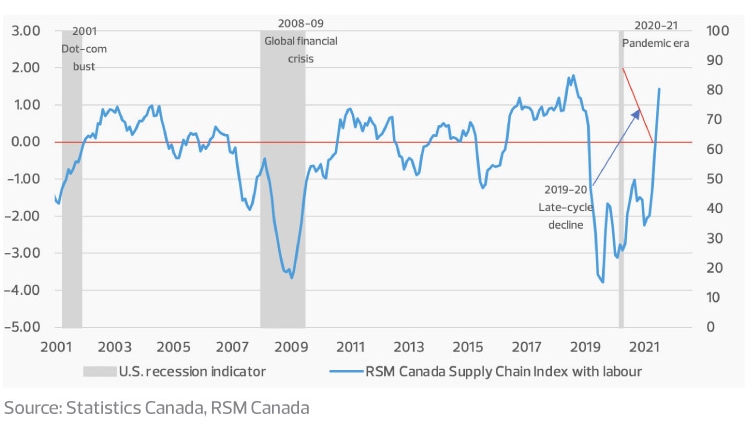

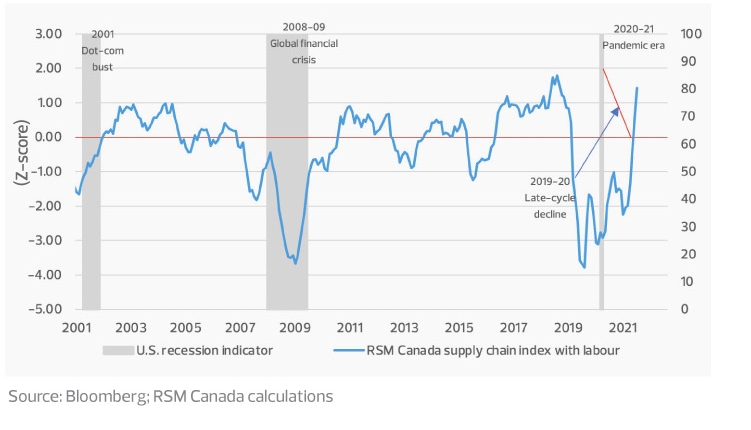

Supply chains

The RSM Canada Supply Chain Index turned positive in June, to 0.51, for the first time since before the pandemic and improved to 1.42 in July.

Inventory has finally improved across the board as back-ordered goods from last year arrive. Delivery times and prices have also improved. The increase in inventory is coupled with a slowdown in demand among consumers as they shift spending toward services.

Consumers can expect fewer empty shelves, more abundant inventory and more discounts in the fall as spending wanes.

Still, even with the recent movement toward deglobalization among businesses, the global supply chain remains vulnerable. Another global shock could send the RSM Canada Supply Chain Index back into negative territory. Worker shortages in warehouses, last-mile delivery services and trucking will continue to pose challenges, especially since consumers’ embrace of online shopping seems to be here to stay.

That said, for now, the supply chain is healthy, and the RSM index could stay positive over the next few months as producers grapple with too much—rather than too little—inventory.

RSM Canada supply chain index

Industrial production

The Prairie provinces have been leading the economy because of strong global demand for energy and rare metals. Industrial production grew by 5.39 per cent on a year-over-year basis in the second quarter, well above the pre-pandemic level, and is expected to end the year on a high note.

As the global markets anticipate a recession and consumer demand slows, industrial production might diminish in subsequent months.

The takeaway

An economic slowdown is not only inevitable amid the tightening cycle and rising interest rates, but it is also needed to combat high inflation.

Heading into next year, expect the economy to stagnate if not contract.

Risks remain that can push the economy into a recession. The most likely catalyst is Russia’s war in Ukraine and its effect on the prices of energy, food and rare minerals. Another potential catalyst is a debt or health crisis in China. These global shocks would undoubtedly spill over into the Canadian economy.

Supply chain timing issues will further distort economic growth. Canadians could continue to face high prices of food, energy and housing, which means deteriorating purchasing power and consumer spending.

RSM contributors

The Real Economy Canada

A quarterly economic report for middle market business leaders.

Industry insights

Industry-specific insights for the middle market.